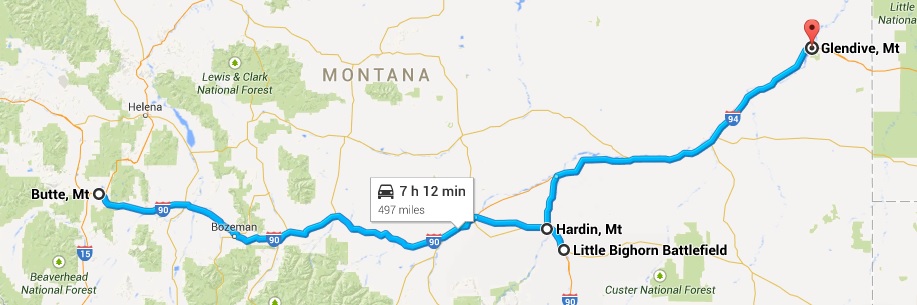

Little Big Horn National Monument sets in south central Montana far away from any large cities. We stayed overnight in Hardin, MT about 16 miles away on the edge of the Crow Agency land.

Paralleling (roughly) the highway between Hardin and the monument is a railroad track which might not generally be notable but this particular day there was a convoy of track maintenance equipment on the move and we got a couple of pictures since we usually see this type of equipment waiting to go rather than moving down the track.

Little Big Horn National Monument memorializes the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry and the Sioux and Cheyenne in a famous battle. During the course of our visit, we heard about the actual battle as well as some perspective on how the battle came to be.

For the most part, the battlefield is just the landscape. There are markers, a road, the visitors’ center and a veterans’ cemetery. It is a place where quiet introspection and retrospection is possible.

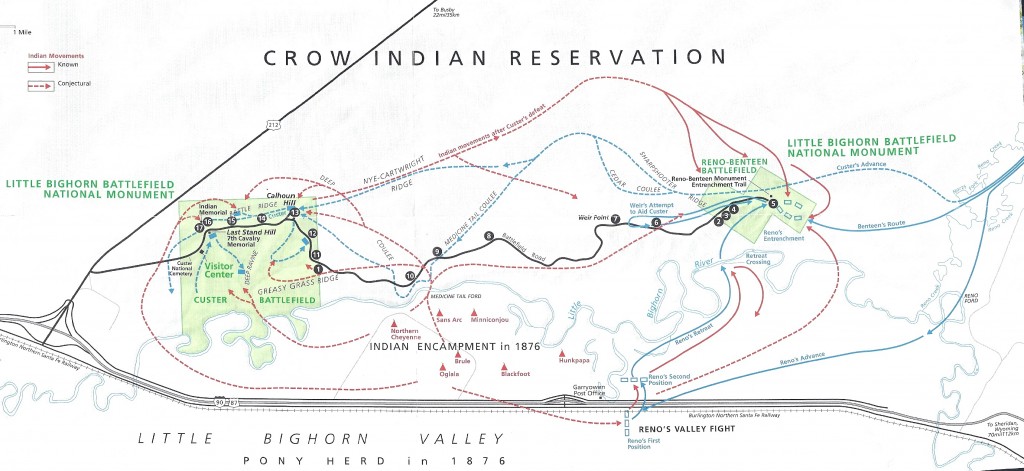

The map above is from the NPS information sheet. I suggest you enlarge it in a separate window or tab for reference.

At our hotel the night before, one of the other guests told us about the interpretive ranger presentation and recommended we attend. Ranger Interpreter Adelson gave quite an animated presentation of the battle. So animated that at the conclusion, he needed to sit down and recuperate a bit before fielding questions. Very impressive.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn was fought in a landscape of ridges, steep bluffs, and ravines of the Little Bighorn River. The combatants were warriors of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes, battling men of the 7th Regiment of the U.S. Cavalry. The Battle of the Little Bighorn has come to symbolize the clash of two vastly dissimilar cultures: the buffalo/horse culture of the northern plains tribes, and the highly industrial/agricultural based culture of the U.S. This battle was not an isolated soldier versus warrior confrontation, but part of a much larger strategic campaign designed to force the capitulation of the nonreservation Lakota and Cheyenne.

In 1868, many, but not all, Lakota leaders agreed to a treaty, known as the Fort Laramie Treaty that created a large reservation in the western half of present day South Dakota and required that they give up their nomadic life and settle into a stationary life, dependent on Government-supplied subsidies. The stationary life on the reservation would have the added benefit of avoiding conflict with other tribes in the region, with settlers, and with railroad surveys. Lakota leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse rejected the reservation system as did many roving bands of hunters and warriors and felt no obligation to conform to the treaty restrictions, or to limit their hunting to the land assigned by the treaty. Their sporadic forays off the set aside lands brought them into conflict with settlers and enemy tribes outside the treaty boundaries.

Tension escalated in 1874, when Lt. Col. Custer was ordered to make an exploration of the Black Hills inside the boundary of the Great Sioux Reservation. He was to map the area including identifying a suitable site for a future military post. During the expedition, professional geologists discovered deposits of gold. Word of the discovery of mineral wealth caused an invasion of miners and entrepreneurs to the Black Hills in direct violation of the treaty of 1868. The government made attempts to keep the settlers out of the Black Hills but that was unsuccessful. The U.S. negotiated with the Lakota to purchase the Black Hills, but the offered price was rejected by the Lakota as the land was sacred to the Indians. The climax came in the winter of 1875, when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs issued an ultimatum requiring all Sioux to report to a reservation by January 31, 1876. The deadline came with virtually no response from the Indians, and matters were handed to the military.

General Philip Sheridan, commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, devised a strategy that committed several thousand troops to find and to engage the Lakota and Cheyenne, who now were considered “hostile”, with the goal of forcing their return to the Great Sioux Reservation. The campaign was set in motion in March, 1876, when the Montana column, a 450 man force of combined cavalry and infantry commanded by Colonel John Gibbon, marched out of Fort Ellis near Bozeman, Montana. A second force, numbering about 1,000 cavalry and infantry and commanded by General George Crook, was launched during the last week of May, from Fort Fetterman in central Wyoming. In the middle of May, a third force, under the command of General Alfred Terry, marched from Fort Abraham Lincoln, Bismarck, Dakota Territory, with a command comprised of 879 men. The bulk of this force was the 7th Cavalry, commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

It was expected that any one of these three forces would be able to deal with the 800-1,500 warriors they likely were to encounter. The three commands of Gibbon, Crook, and Terry were not expected to launch a coordinated attack on a specific Indian village at a known location. Inadequate, slow, and often unpredictable communications hampered the army’s coordination of its expeditionary forces. Furthermore, it must be remembered that their nomadic hunting put the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies constantly on the move. No officer or scout could be certain how long a village might remain stationary, or which direction the tribe might choose to go in search of food, water, and grazing areas for their horses.

The tribes had come together for a variety of reasons. The well watered region of the Powder, Rosebud, Bighorn, and Yellowstone rivers was a productive hunting ground. The tribes regularly gathered in large numbers during the spring to celebrate their annual sun dance ceremony. The sun dance ceremony had occurred about two weeks earlier near present day Lame Deer, Montana. During the ceremony, Sitting Bull received a vision of soldiers falling upside down into his village. He prophesied there soon would be a great victory for his people.

On the morning of June 25, the camp was ripe with rumors about soldiers on the other side of the Wolf Mountains, 15 miles to the east, yet few people paid any attention. In the words of Low Dog, an Oglala Sioux, “I did not think anyone would come and attack us so strong as we were.”

On June 22, General Terry decided to detach Custer and his 7th Cavalry to make a wide flanking march and approach the Indians from the east and south. Custer was to act as the hammer, and prevent the Lakota and their Cheyenne allies from slipping away and scattering, a common fear expressed by government and military authorities. General Terry and Colonel Gibbon, with infantry and cavalry, would approach from the north to act as a blocking force or anvil in support of Custer’s far ranging movements toward the headwaters of the Tongue and Little Bighorn Rivers. The Indians, who were thought to be camped somewhere along the Little Bighorn River, “would be so completely enclosed as to make their escape virtually impossible”.

On the evening of June 24, Custer established a night camp twenty-five miles east of where the battle would take place on June 25-26. The Crow and Arikara scouts were sent ahead, seeking actionable intelligence about the direction and location of the combining Lakota and Cheyenne. The returning scouts reported that the trail indicated the village turned west toward the Little Bighorn River and was encamped about twenty-five miles west of the June 24 camp. Custer ordered a night march that followed the route that the village took as it crossed to the Little Bighorn River valley. Early on the morning of June 25, the 7th Cavalry Regiment was positioned near the Wolf Mountains about twelve miles from the Lakota/Cheyenne encampment along the Little Bighorn River. Today, historians estimate the village numbered 8,000, with a warrior force of 1,500-1,800 men. Custer’s initial plan had been to conceal his regiment in the Wolf Mountains through June 25th, which would allow his Crow and Arikara scouts time to locate the Sioux and Cheyenne village. Custer then planned to make a night march, and launch an attack at dawn on June 26; however, the scouts reported the regiment’s presence had been detected by Lakota or Cheyenne warriors. Custer, judging the element of surprise to have been lost, feared the inhabitants would attack or scatter into the rugged landscape, causing the failure of the Army’s campaign. Custer ordered an immediate advance to engage the village and its warrior force.

At the Wolf Mountain location, Custer ordered a division of the regiment into four segments: the pack train with ammunition and supplies, a three company force (125) commanded by Captain Frederick Benteen, a three company force (140) commanded by Major Marcus Reno and a five company force (210) commanded by Custer. Benteen was ordered to march southwest, on a left oblique, with the objective of locating any Indians, “pitch into anything” he found, and send word to Custer. Custer and Reno’s advance placed them in proximity to the village, but still out of view. When it was reported that the village was scattering, Custer ordered Reno to lead his 140 man battalion, plus the Arikara scouts, and to “pitch into what was ahead” with the assurance that he would “be supported by the whole outfit”.

The Lakota and Cheyenne village lay in the broad river valley bottom, just west of the Little Bighorn River.

As instructed by his commanding officer, Reno crossed the river about two miles south of the village and began advancing downstream toward its southern end. Though initially surprised, the warriors quickly rushed to fend off Reno’s assault. Reno halted his command, dismounted his troops and formed them into a skirmish line which began firing at the warriors who were advancing from the village. Mounted warriors pressed their attack against Reno’s skirmish line and soon endangered his left flank. Reno withdrew to a stand of timber beside the river, which offered better protection. Eventually, Reno ordered a second retreat, this time to the bluffs east of the river. The Sioux and Cheyenne, likening the pursuit of retreating troops to a buffalo hunt, rode down the troopers. Soldiers at the rear of Reno’s fleeing command incurred heavy casualties as warriors galloped alongside the fleeing troops and shot them at close range, or pulled them out of their saddles onto the ground.

Reno’s now shattered command recrossed the Little Bighorn River and struggled up steep bluffs to regroup atop high ground to the east of the valley fight. Benteen had found no evidence of Indians or their movement to the south, and had returned to the main column. He arrived on the bluffs in time to meet Reno’s demoralized survivors. A messenger from Custer previously had delivered a written communication to Benteen that stated, “Come on. Big Village. Be Quick. Bring Packs. P.S. Bring Packs.” An effort was made to locate Custer after heavy gunfire was heard downstream. Led by Captain Weir’s D Company, troops moved north in an attempt establish communication with Custer.

Assembling on a high promontory (Weir Point) a mile and a half north of Reno’s position, the troops could see clouds of dust and gun smoke covering the battlefield. Large numbers of warriors approaching from that direction forced the cavalry to withdraw to Reno Hill where the Indians held them under siege from the afternoon of June 25, until dusk on June 26. On the evening of June 26, the entire village began to move to the south.

The next day the combined forces of Terry and Gibbon arrived in the valley bottom where the village had been encamped. The badly battered and defeated remnant of the 7th Cavalry was now relieved. Scouting parties, advancing ahead of General Terry’s command, discovered the dead, naked, and mutilated bodies of Custer’s command on the ridges east of the river. Exactly what happened to Custer’s command never will be fully known. From Indian accounts, archeological finds, and positions of bodies, historians can piece together the Custer portion of the battle, but not with absolute certainty.

It is known that, after ordering Reno to charge the village, Custer rode northward along the bluffs until he reached a broad coulee known as Medicine Tail Coulee, a natural route leading down to the river and the village. Archeological finds indicate some skirmishing occurred at Medicine Tail ford. For reasons not fully understood, the troops fell back and assembled on Calhoun Hill, a terrain feature on Battle Ridge. The warriors, after forcing Major Reno to retreat, now began to converge on Custer’s maneuvering command as it forged north along what, today, is called Custer or Battle Ridge.

Dismounting at the southern end of the ridge, companies C and L appear to have put up stiff resistance before being overwhelmed. Company I perished on the east side of the ridge in a large group, the survivors rushing toward the hill at the northwest end of the long ridge. Company E may have attempted to drive warriors from the deep ravines on the west side of the ridge, before being consumed in fire and smoke in one of the very ravines they were trying to clear. Company F may have tried to fire at warriors on the flats below the National Cemetery before being driven to the Last Stand Site.

About 40 to 50 men of the original 210 were cornered on the hill where the monument now stands. Hundreds of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors surrounded them. Toward the end of the fight, the soldiers killed their horses and used their bodies as defensive shielding. In the end, the warriors quickly rushed to the top of the hill, cutting, clubbing, and stabbing the last of the wounded. Superior numbers and overwhelming firepower brought the Custer portion of the Battle of the Little Bighorn to a close.

The battle was a momentary victory for the Sioux and Cheyenne. General Phil Sheridan now had the leverage to put more troops in the field. Lakota Sioux hunting grounds were invaded by powerful Army expeditionary forces, determined to pacify the Northern Plains and to confine the Lakota and Cheyenne to reservations. Most of the declared “hostiles” had surrendered within one year of the fight, and the Black Hills were taken by the U.S. without compensation.

General Custer has often been portrayed as arrogant and somewhat foolish for starting the attack and maybe he was. We were somewhat shocked to overhear a woman telling the child with her to put back the Custer souvenir “You don’t want that. He’s an asshole.” . In the War of Northern Aggression/War Between the States/Civil War (mixed audience here), he was noted for fighting against the odds and winning. His widow was given the table used to sign the surrender papers as testament to his role in ending the war militarily. The National Park Service has a discussion of General Custer’s military career here. There is also a discussion of Chief Sitting Bull here.

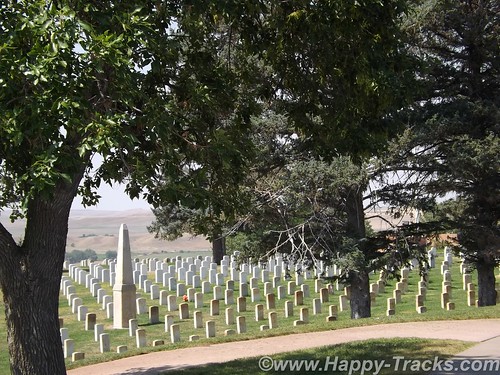

In 1879, the Little Bighorn Battlefield was designated a national cemetery administered by the War Department. In 1881, a memorial was erected on Last Stand Hill, over the mass grave of the Seventh Cavalry soldiers, U.S. Indian Scouts, and other personnel killed in battle. In 1940, jurisdiction of the battlefield was transferred to the National Park Service. These early interpretations honored only the U.S. Army’s perspective, with headstones marking where each fell.

The essential irony of the Battle of the Little Bighorn is that the victors lost their nomadic way of life after their victory. Unlike Custer’s command, the fallen Lakota and Cheyenne warriors were removed by their families, and “buried” in the Native American tradition, in teepees or tree-scaffolds nearby in the Little Bighorn Valley. The story of the battle from the Native American perspective was largely told through the oral tradition.

In 1991, the U. S. Congress changed the name of the battlefield and ordered the construction of an Indian Memorial.

In 1996, the National Park Service – guided by the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Advisory Committee, made up of members from the Indian nations involved in the battle, historians, artists and landscape architects – conducted a national design competition. In 1997 a winning design was selected.

Note the term Indian. Its used a lot out here rather than Native Americans or individual nation names. It’s not my intent to offend.

- 7 December 1886: The site was proclaimed National Cemetery of Custer’s Battlefield Reservation to include burials of other campaigns and wars. The name has been shortened to “Custer National Cemetery”.

- 5 November 1887: Battle of Crow Agency, three miles north of Custer battlefield

- 14 April 1926: Reno-Benteen Battlefield was added

- 1 July 1940: The site was transferred from the United States Department of War to the National Park Service

- 22 March 1946: The site was redesignated “Custer Battlefield National Monument”.

- 15 October 1966: The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[4]

- 11 August 1983: A wildfire destroyed dense thorn scrub which over the years had seeded itself about and covered the site.[5] This allowed archaeologists access to the site.

- 1984, 1985: Archaeological digging on site.

- 10 December 1991: The site was renamed Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument by a law signed by President George H. W. Bush

Custer National Cemetery is located at the National Monument grounds. These veterans are from later wars. They stopped accepting new internees in 1978 due to space constraints.

Here are a couple of other Battlefield maps. Open in another tab/window From Smithsonian Magazine

From Mohican Press

You can see all of the pictures from this leg of the trip here.

We invite you to continue along with us and hope you enjoy the account!

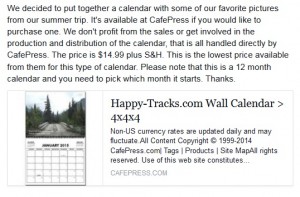

Don’t forget the trip calendar we put together at CafePress. We think it turned out pretty well and would make a great holiday gift.